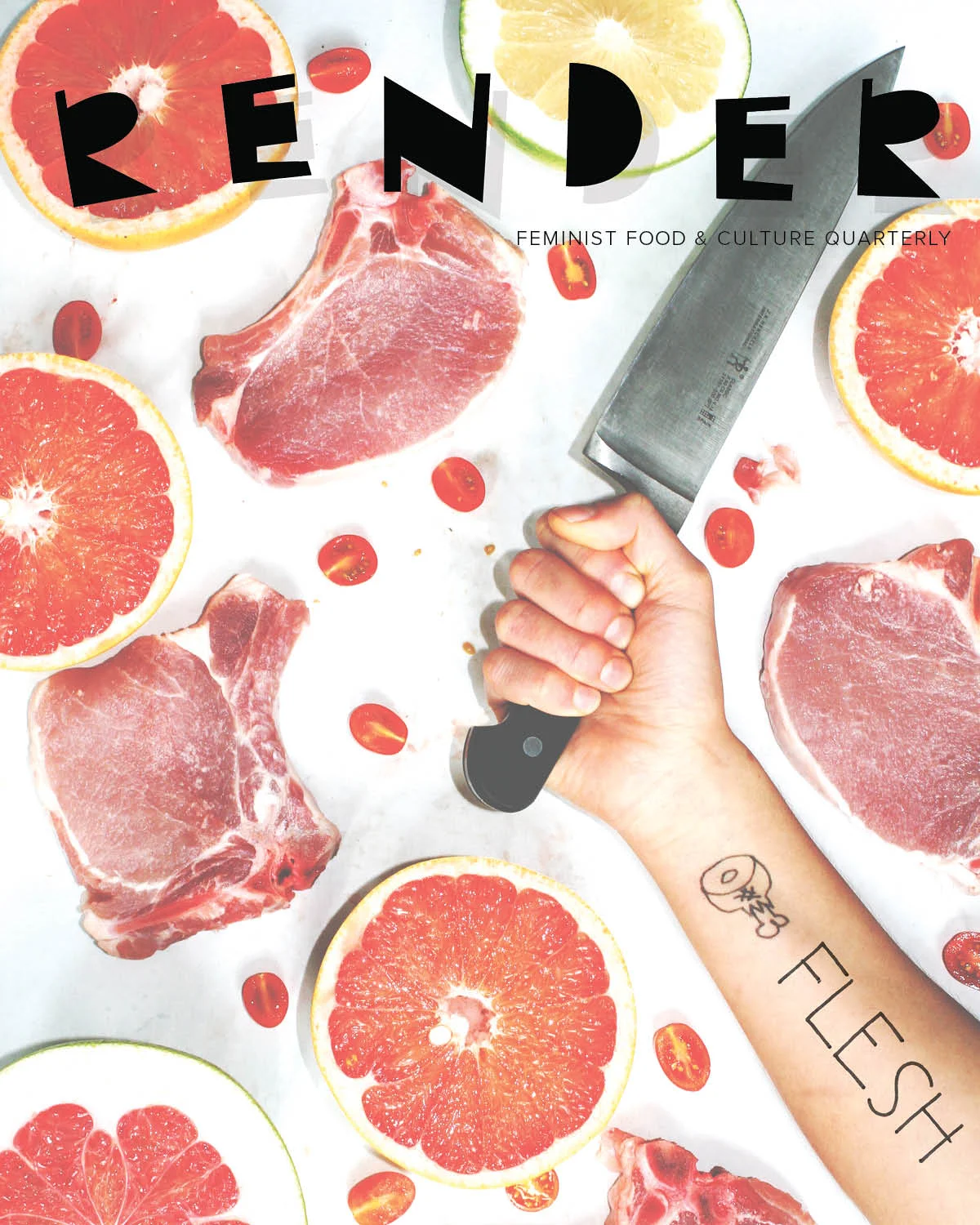

Illustration by Molly Mendoza.

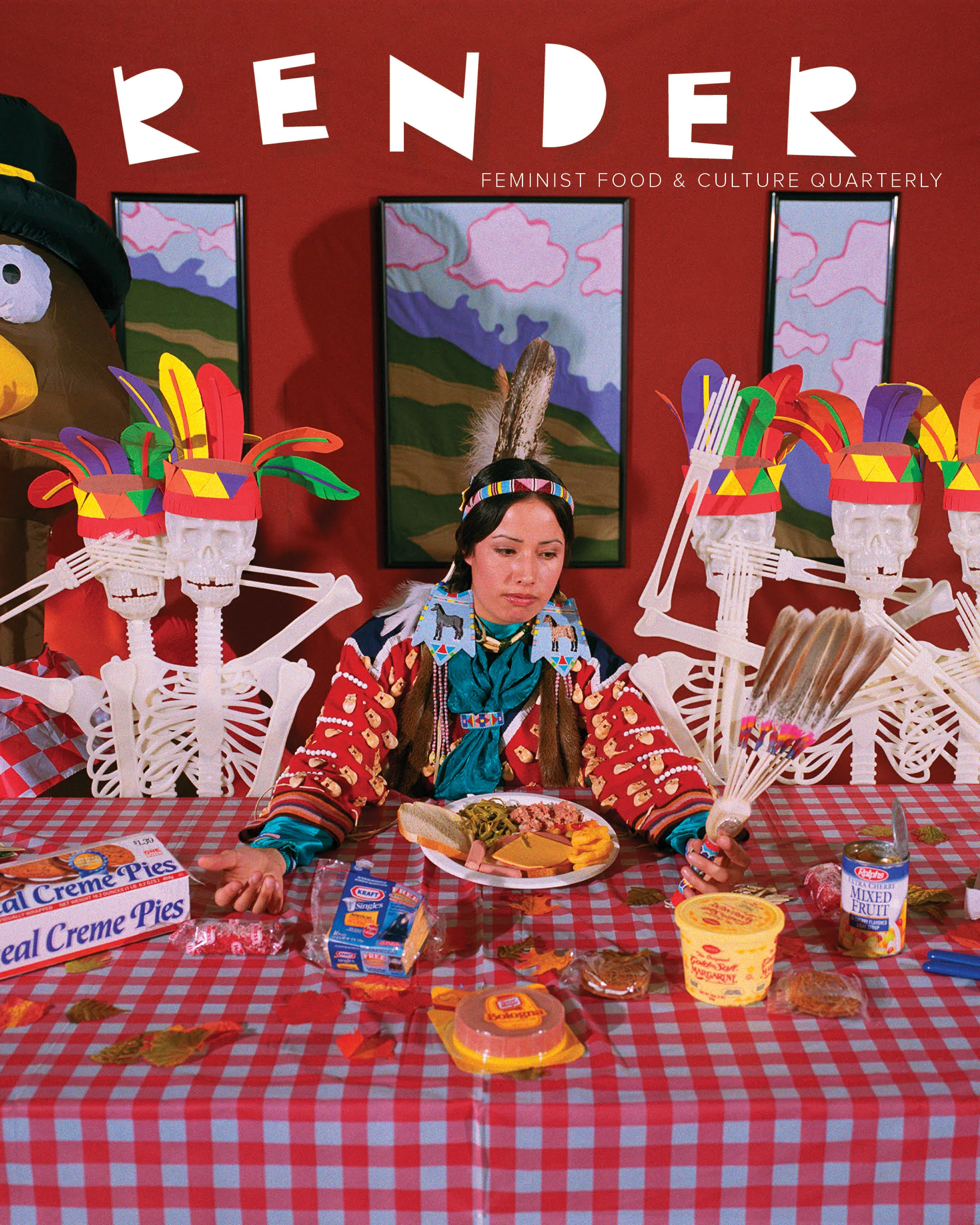

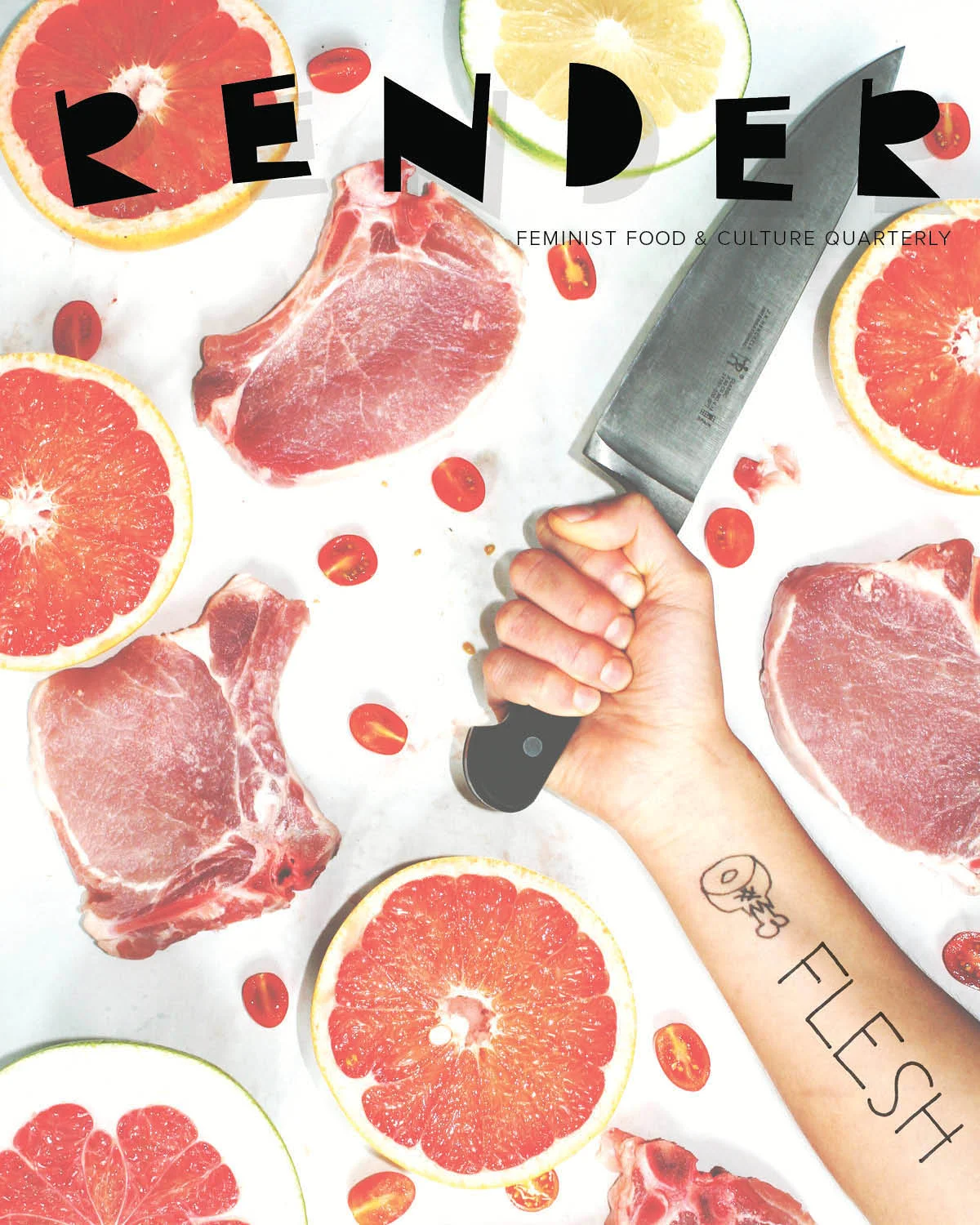

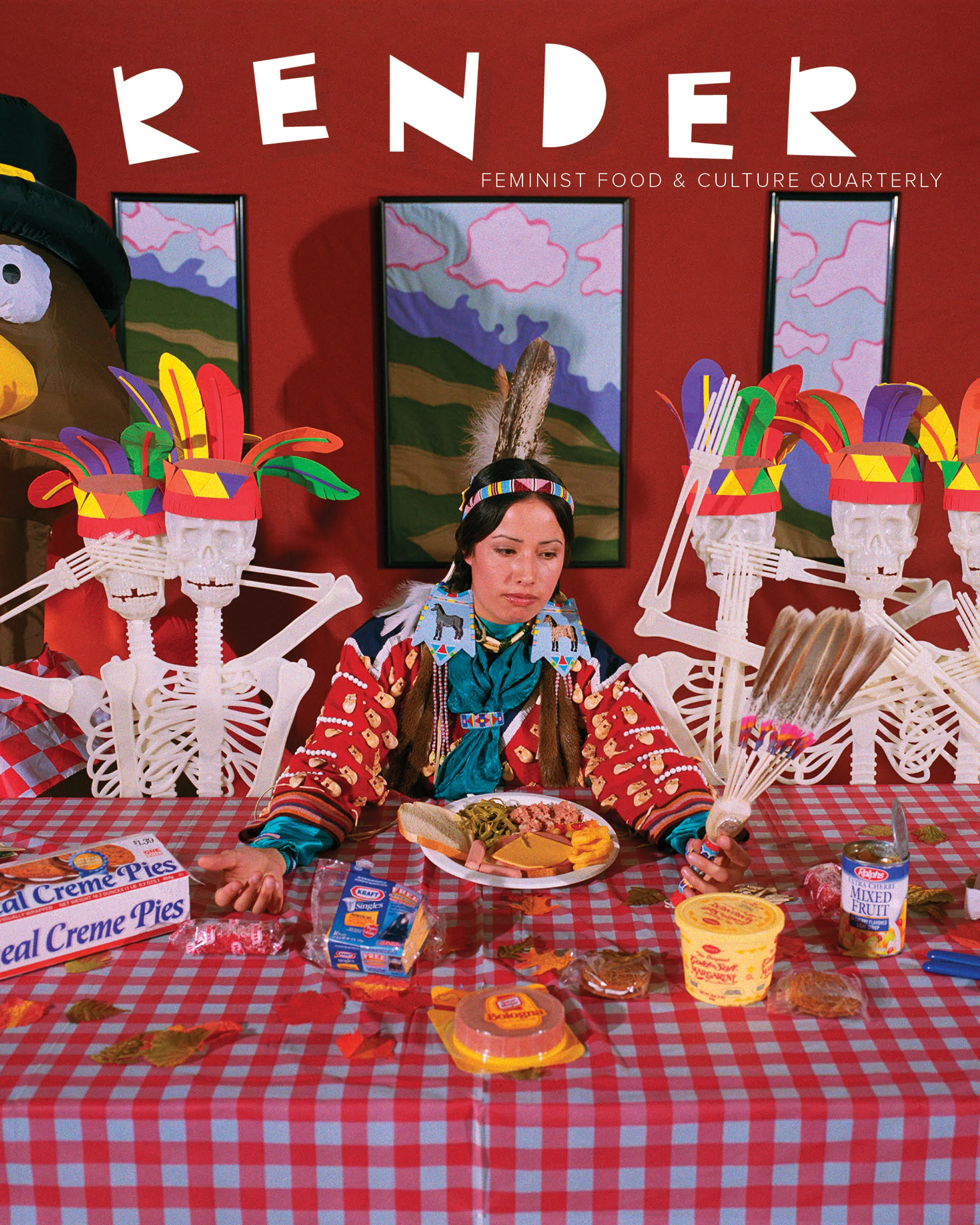

Welcome to Savor the Science! In each Savor the Science, RENDER’s resident chemist, Claire Lower, will explore culinary questions through a scientific lens, perfecting recipes and demystifying techniques. Theories and reactions will be discussed and experiments will be performed; it’s like your high school chemistry class, only edible. Twice a month, Claire will take a scientific concept (such as the acid-base reactions in baking, macerating, or Maillard browning), explain it in a way that would make Bill Nye proud (hopefully), and then provide an edible experiment which allows you to demonstrate your new scientific food knowledge.

There is no right way to make gumbo, but there are definitely many wrong ways to make gumbo. Louisiana’s state dish is uniquely its own thing, somewhere between a soup and stew without being either one. No two bowls are the same, though it is commonly agreed upon that there should be (at the very least) a flavorful and aromatic stock, some sort of protein (usually meat or seafood, no pork unless it’s cured), seasonal vegetables (most commonly onions, bell peppers, and celery), and some sort of thickening agent. It is usually served over rice.

Besides being absolutely delicious, it’s an interesting study in southern cuisine. Perhaps better than any other single dish, gumbo highlights the intersectionality of southern food with clear ties to African, Native American, and European cultures. These ties are most apparent in the thickening agents.

When making gumbo, one has three different thickeners at their disposal: roux, filé powder, and okra. Each has a different origin, and each thickens in a different manner. Some recipes only call for one, some for two, some all three, and there are as many ways to make gumbo as there are gumbo cooks. Much time could be spent discussing the geographical and cultural origins of this dish and its thickeners – even the origin of the name “gumbo” is still debated – but we are (of course) going to focus on how, from a chemical perspective, each of these agents increases the viscosity of this Louisiana staple.

Okra

Okra is a flowering plant of the mallow family with green edible seed pods. Though its exact place of origin is disputed, it is believed to have been brought to the Caribbean and U.S. in the 1700’s by enslaved Africans. According to Robert Moss in his article for Serious Eats titled “The Real Story of Gumbo, Okra, and Filé,” the pod isn’t just responsible for the dish’s consistency, it’s responsible for the name:

“In several West African languages, the word for okra is ki ngombo, or, in its shortened form, gombo. Early on, the word was frequently used alongside 'okra' by English writers. In the 1840s, when okra was just starting to be grown widely outside the coastal South, newspaper ads commonly offered seeds for 'Okra or Gombo.' 'Gombo' is still the French word for okra today.”

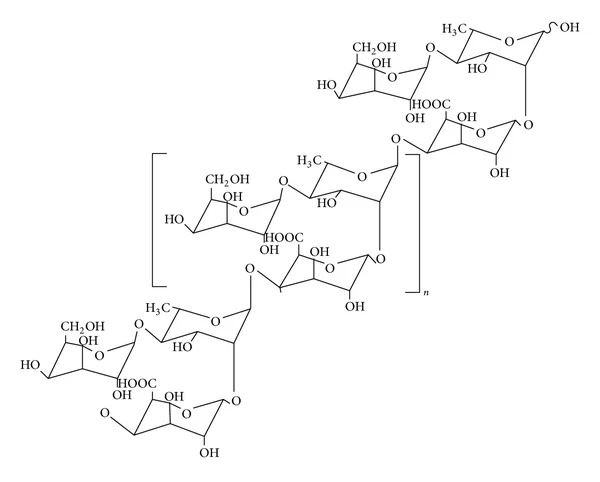

The plant doesn’t just lend its name to this delicious dish, it gives it body. Unfortunately, okra is often maligned for the same properties that make it such a good thickener: its sliminess. If you’ve ever had boiled okra, you have undoubtedly noticed the thick and viscous goo that ruins an otherwise delicious bite. That goo is called mucilage, a polymeric (chain of repeating molecular structures) carbohydrate that is found in nearly all plants. Some plants (such as okra, kelp and aloe vera) have noticeably higher concentrations than others. The structure of the mucilage found in okra looks like this:

Mucilage is edible, and its slimy or viscous characteristics make it perfect for demulcent or thickening applications. In the case of okra (or kelp), heating increases the viscosity of mucilage of the plant, and the result is very gooey. This isn’t a great quality if you're sitting down to a mountain of boiled okra, but it’s a highly desirable characteristic when you want to thicken up your gumbo.

Like so many other aspects of gumbo, exactly when the okra is added isn’t clearly defined. There are recipes that start with sauteed okra and recipes where it’s simmered for only the last fifteen minutes of the entire process. No matter when it’s added, you can count on okra to provide body and flavor.

Filé

Filé powder is a spicy, earthy seasoning made from dried and ground sassafras leaves. First used by the Choctaw tribe of the American South as a spice, it was later adopted by Creole chefs as a thickening agent.

Like okra, sassafras also possesses a good deal of mucilage. So much that it is only sprinkled into bowls of gumbo after the concoction is done cooking. If exposed to too much heat (or if too much of it is added), the filé will clump into a stringy mess. This characteristic is what gives the powder its name: filé means “stringy” or “thready” in French.

It is thought to have been originally added to gumbo as a substitute for okra in the winter, when the vegetable wasn’t in season, and there is a clear culinary line drawn between gumbo made with okra and filé gumbo.

Roux

Roux thickens in a way that is completely different from either okra or filé, as flour is devoid of mucilage (something I am thankful for, because think of the baked goods). It is essentially fried flour. To make a roux, you simply combine equal parts fat and flour and cook until it achieves its desired color. For gumbo, you want to aim for a dark, reddish brown color. The darker the roux, the nuttier the flavor.

But how does it thicken? When you apply heat to flour, it starts to break down and release starch. This starch absorbs liquid and swells, thickening your soup, sauce, or gravy. The fat helps by coating individual flour particles, preventing them from clumping together and allowing each particle to swell independently. Starch is made up of amylose and amylopectin, which look like this:

Amylose

and this:

Amylopectin

A dark roux is a crucial element of the gumbo’s flavor, but a lighter roux is much better for increasing viscosity. Though heat initially releases the starch from the flour, it will eventually cause it to break down and lose some of its thickening properties.

If you like a thicker gumbo, you can always increase the volume of the roux, throw some okra in the pot, or add filé powder after cooking.

I grew up eating gumbo. Though we’re not from Louisiana (my mom was raised just across the river, in Natchez, Mississippi) each member of the family has their own way of making this classic southern dish. My family is a roux family, and my mother has never made her gumbo with okra or filé. Like me, she has a degree in chemistry and – also like me – she never measures anything when cooking. I suspect that this refusal to measure is a sort of symbolic rebellion against four years of weighing everything to a tenth of a milligram, but I could be over thinking it.

The point is, my mother’s gumbo is never the same twice. Trying to get a “recipe” from her was a little difficult. It ended up being less of a “recipe” and more of a “vague phone conversation with lots of caveats.”

Before I share this with you, it is important you understand that there are a few ways in which our gumbo is atypical. These are:

- Unless we are in the South (we both now live on the west coast), my mother and I use red and yellow bell peppers. Gumbo is supposed to be made with green, but we have both found west coast green bell peppers to be far too bitter. We suspect that it has something to do with the pH of the soil, but no studies have been made.

- In Cajun and Creole cooking, the “Holy Trinity” is onions, bell peppers, and celery in roughly equal amounts. It is used in everything, and a true Louisiana cook would never think of omitting any one of the three. Unfortunately, my mother and I both loathe celery. As such, we omit it, though this is technically incorrect.

- Though my mother never added okra to her gumbo, I initially decided to add some in to help thicken it up (hers was usually on the thin side, which is totally fine, but this post is about thickening). However, the roux worked so well, I ended up omitting it. This may render it a little less “authentic,” but oh well. Please don’t yell at me.

Alright. Let’s do this. Though mine didn’t turn out exactly like “mamma used to make” (it was much thicker, almost like gravy), it was pretty damn close. The beauty of gumbo is that it’s somewhat improvisational, so feel free to play around with the type of fat (just make sure it has a high smoke point), meat, and seasonings.

Claire’s Chicken and Sausage Gumbo (based on a semi-confusing phone conversation she had with her mother):

Ingredients:

4 pounds of bone-in, skin-on, dark meat chicken

1 package of Andouille sausage, cut into coins

¼ cup chicken fat (rendered out when you cook the chicken)

½ cup of vegetable shortening (you can use all chicken fat if you have enough)

¾ cups of all-purpose flour

2-3 garlic cloves, finely chopped

1 large onion, chopped

2 large bell peppers, chopped (I used one red and one yellow)

2 stalks of celery, chopped (though I did not do this)

All vegetable bits and ends you don’t plan on eating, such as celery leaves, onion ends and skin, etc.

1 bay leaf

2 teaspoon Cajun seasoning, preferably Tony Cachere’s

1 teaspoon of granulated garlic

1 teaspoon of granulated onion

Instructions:

Brown your chicken, skin down, in a heavy bottomed all-clad or cast iron pan. Once the skin is crispy, transfer to a baking dish and let finish cooking (skin side up) in the oven at 475 F for 18-20 minutes.

Pour off the chicken fat rendered out while browning and set aside. You should have about a ¼ of a cup. Deglaze the pan with water or chicken stock, and transfer to a stock pot.

Once the chicken is done cooking, let cool and pull every bit of meat you can off the bones. Transfer all bones, skin, and anything that isn’t meat into the stockpot and throw in your vegetable scraps, along with a bay leaf. Add enough water to barely cover the pot’s contents and simmer until you have a rich, flavorful stock (about two hours). Strain and set aside.

Brown the sausage and set aside.

Melt your fat over medium high heat and gradually add in the flour, whisking constantly to prevent lumps. Once all the flour is incorporated, decrease the heat to low and cook for 45-60 minutes, stirring frequently, until your roux is a dark reddish brown. It should look like melted milk chocolate:

Once your roux is nice and dark, add in the chopped vegetables and garlic. Stir to coat and continue to cook on low until the vegetables are soft and the onions are translucent (about ten minutes).

Slowly pour in the stock, stirring continuously to prevent clumping. Add in chicken, sausage, granulated garlic and onion, and Cajun seasoning. Heat until warm and serve over rice and top with hot sauce or more Tony Cachere's to taste.