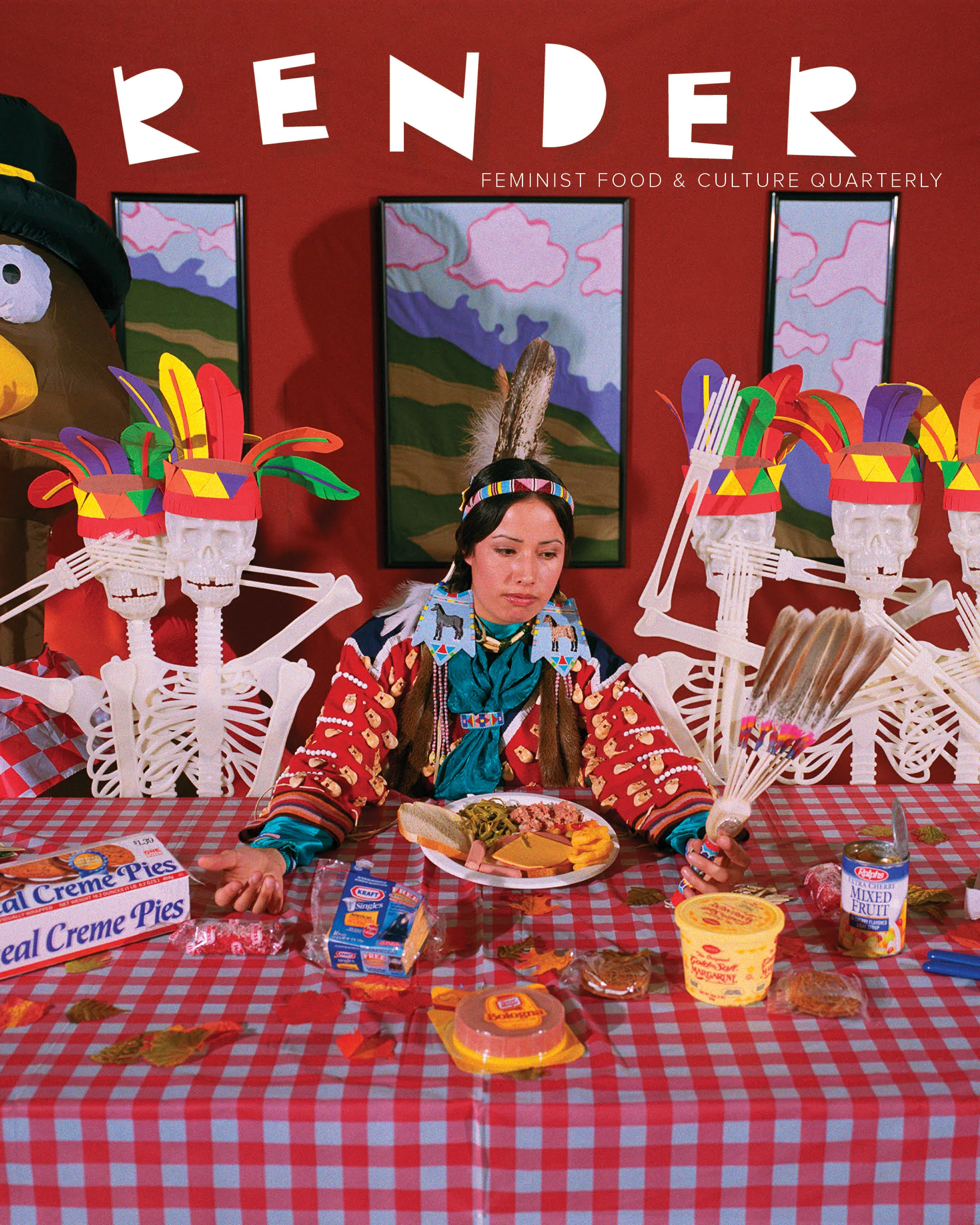

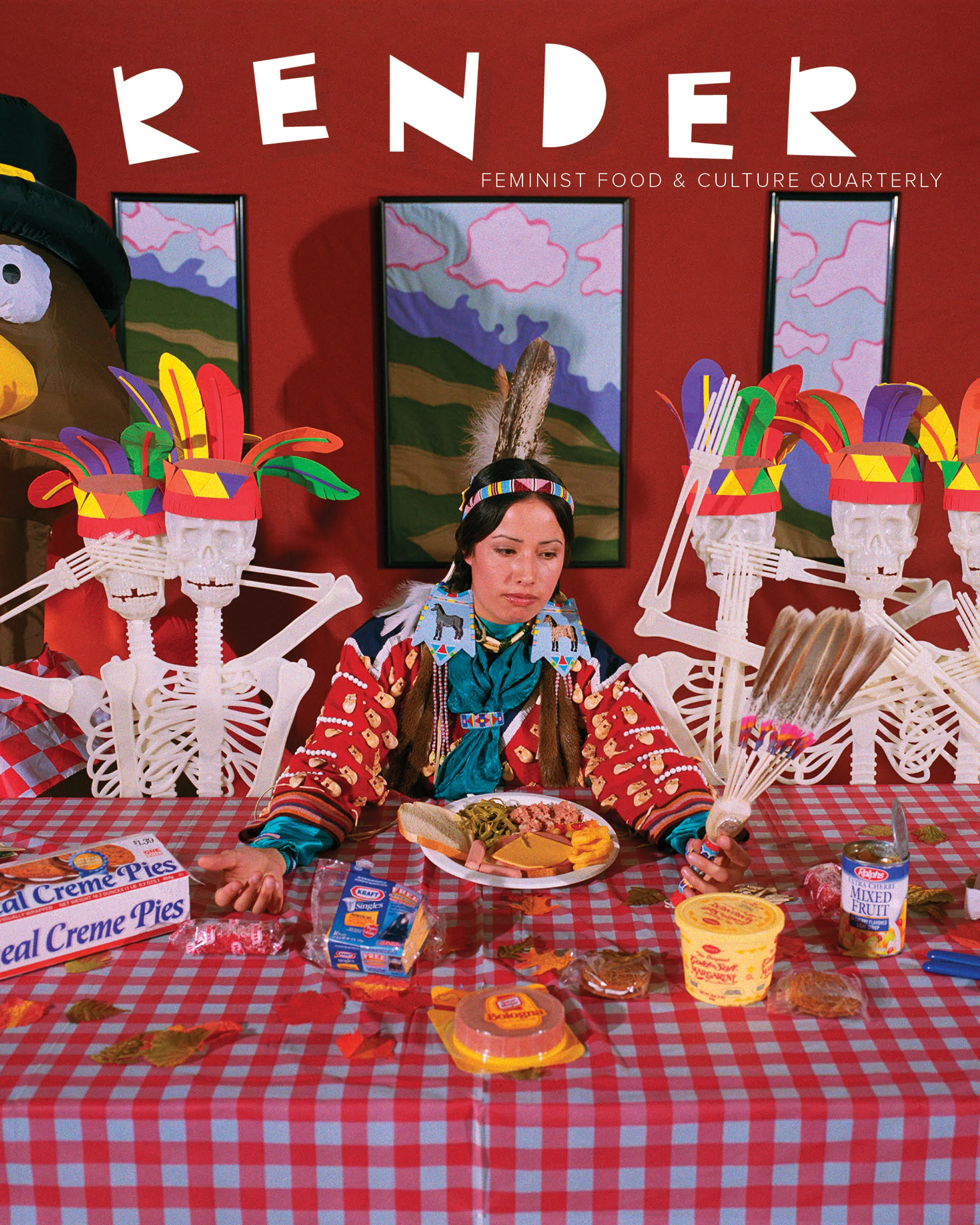

Photo from 2014 South Korean kimchi contest taken by Jeon Han.

In each installment of Breaking Bread, Phylisa Wisdom will discuss gastrodiplomacy—using the history of different foods, and eating and cooking those foods, to foster understanding and cooperation between cultures. Think of it as breaking bread to break down barriers. We’ll explore who gastrodiplomats are and what they’re doing – or cooking – to engage in dialogue with, or about, other cultures and countries. The column will feature interviews with sassy changemakers, recipes from chefs involved in gastrodimplocatic efforts, and analysis of effective efforts (and sometimes wretched failures) from all over the world. We’re unapologetically in favor of talking politics at the dinner table.

In April 2009, the government of the Republic of Korea (ROK) designed and implemented the Korean Cuisine to the World Campaign with the goal of quadrupling the number of Korean restaurants outside of Korea by 2017. ROK’s Ministry of Food, Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries has dedicated US $40 billion to an effort that would prioritize increasing the number of international Korean restaurants to 40,000. According to an article in the New York Times, the ultimate goal of the campaign is for Korean food to place in the top five international cuisines (even though no formal international food ranking system exists). The international publicity campaign to promote Korean food, or hansik, extends beyond opening Korean restaurants; the government has also launched a plan to promote Korean celebrity chefs and opened the first World Institute of Kimchi in 2010.

Last November, Korean-American chef Edward Lee and reality TV star Audrina Patridge filmed a segment for NBC’s 1st Look, a food-travel show tasked with introducing Americans to interesting international food culture and trends. The segment, unsurprisingly, was sponsored by the Korean Food Foundation, one arm of the Korean Cuisine to the World Campaign. In a Food Republic article on the segment, chef/owner of Chicago’s Parachute, Beverly Kim, is quoted as saying, “It will only be a matter of time before kimchi is as common knowledge as salsa.”

If Korean Cuisine to the World has one overarching aim, it is to make Korean cuisine more pervasive the world over, and it appears to be working. But a gastrodiplomatic mission such as this affects more than just the tastebuds of foreign publics; one of the reasons this effort has been so well funded is that it also has the power to subtly change the way international audiences view and interact with ROK as a country.

Beyond economic benefits to individuals and a potential spike in tourism, ROK’s official gastrodiplomatic efforts are intended to make the country a more robust soft power, according to Paul Rockower of Levantine Public Diplomacy, who writes extensively on public diplomacy and is an expert in the burgeoning field of gastrodiplomacy. We emailed back and forth, chatting about the ways in which gastrodiplomacy influences policy and international relations. One goal, he said, is stronger nation branding. Nation branding is the application of public relations and corporate branding techniques to nations in hopes of facilitating trade, luring foreign investment, and securing geopolitical influence. “Having a stronger nation brand helps so-called ‘Middle Powers’ like South Korea, Taiwan, Peru and Malaysia, among others, distinguish their uniqueness in the cluttered international landscape. Such countries have turned to cultural diplomacy and gastrodiplomacy as a means to enhance their respective nation brands and increase their soft power.” A stronger, more stable nation brand means increased money, power, and influence, and raising a country’s culinary profile is one way to increase brand recognition.

According the former head of ROK’s Ministry of Food, Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries, Chung Woon-chun,

“Hansik is not just food; it is the root of the country’s philosophy and traditional culture that bears our culture, spirit, and a 5,000 year history. Our ancestors developed a unique food culture that is harmonized with nature. Fermented food, in particular, is healthy since it is made with Korean agricultural products that have strong medicinal effects. The main ingredient is bay salt, created by the earth, water, fire, and wind.”

Woon-chun’s sentiments mirror those of gastrodiplomacy proponents: experiencing cuisine is an introduction to more than flavors; when a person dines in a Korean-owned and operated restaurant, the thinking goes that they are theoretically introduced to other aspects of the culture (or simply the culture through the lens of those running the restaurant). This can include various cultural mores, customer service and hospitality expectations, and alcohol consumption norms. In the case of ROK, Woon-chun hopes that those dining on hansik all over the world recognize the harmonization of the cuisine with nature, the focus on its medicinal benefits, and the 5,000-year historical legacy of the South Korean nation-state. He pointed out the rich cultural history of South Korea and the benefits of fermented food as unique and important to hansik with the hopes that diners may garner awareness simply by consuming the food.

Sam Chapple-Sokol – one of the creators of the gastrodiplomacy college course previously discussed in this column – has said that international restaurants abroad act as unofficial embassies (when owned by expats of that country), and that’s exactly why governments want to invest in them. Rockower agrees: “Restaurants serve as outposts of culinary culture abroad, and as such, restaurants can make foreign cultures more familiar because of the tangible connection created to another country's culture through food.” The foreign-food-restaurant-as-unofficial-embassy-model is ideal for governments because they are private sector businesses and independently run, thus they are disconnected from official governmental work and able to reach wider audiences. However, this model requires diners to be discerning enough to identify which pieces of a dining experience are “cultural” and which are simply the way a business is run by individual business owners.

If a Korean BBQ restaurant has slow service, diners may erroneously think that says something bigger about Korean culture, too. There is always potential for diners to read any part of their dining experience as something “authentic” when dining is construed as a “cultural experience.” Requiring an individual or family to be a spokesperson for an entire country is thus an enormous and unrealistic responsibility for many people. When a non-Korean diner goes to an “authentic” Korean-owned restaurant, often the experience is more about the non-Korean diner’s expectations, and the diner may work to fit the experience into their expectation. In her piece “Craving the Other” for Bitch Magazine, Soleil Ho addressed this idea of diner’s consuming foreign food and cuisine in search of foreign authenticity writing,

“Their commonality is their insistence on appreciating a culture that exists mostly in their heads; they share a nostalgia for someone else’s life. Nostalgia traps the things you love in glass jars, letting you appreciate their arrested beauty until they finally die of boredom or starvation. The sought-after object cannot move on from you or depart from the fixed impression that you have imposed upon it. After all, a thing can’t be 'authentic' if it’s allowed the power to change.”

In Jonathan Gold’s 2012 LA Weekly article “60 Korean Dishes Every Angeleno Should Know,” he introduced readers to dishes, but perhaps more interestingly, endeavored to adjust their expectations of the dining experience with Korean restaurant owners and service staff. “The idea of service tends to be different in Korean restaurants from what it is even in other Asian restaurants: The waiters and waitresses are there to take your order, bring you food and fetch the check, period. There will be no discussion of the vegetables in season, or banter about whether the mackerel is better than the cod. The best small restaurants specialize in one or two specialties, and you will be expected to order one of them.” I asked Gold, now L.A. Times food critic, what percentage of Los Angeles’s Korean restaurants are South Korean-owned, in his estimation. He responded via Twitter that it's “100%, more or less.” In this piece, the discussion of Korean dishes is conflated with the discussion about Korean restauranteurs and wait staff. As Korean food gets trendier and continues to be appropriated by non-Korean entrepreneurs, we will have to learn to separate the person from the business, or we risk making gross generalizations about both Korean cuisine and Korean people. The question of what is "authentically" Korean should remain up for discussion despite the ROK's nation branding efforts via food and restaurants.

Wonder Girls (원더걸스) – "K FOOD PARTY." The Wonder Girls were appointed as South Korean food ambassadors.

The Korean Cuisine to the World Campaign is well crafted, and appears to have already made great gains in multiplying Korean restaurants abroad and thus raising the profile of hansik. ROK’s next challenge may be introducing foreign audiences to other aspects of Korean culture so we can better differentiate between Korean cultural tropes based on food consumption and the varied, changing, immensely complicated business that is Korean “culture.” While exposure increases awareness and can encourage positive interaction, an over-familiarity with Korean cuisine based on a limited concept of "Korean culture" may also work to further isolate South Koreans living abroad who are made to represent all of South Korean culture and "tradition."